Rarely have voters at a UK general election been offered such starkly different economic policy platforms to choose from. The parties’ tax proposals epitomise this.

Conservatives

The Conservative manifesto is virtually devoid of proposals for tax changes. That is not necessarily a bad thing: many of us bemoan the constant upheaval that bedevils our tax system.

But they may come to regret their guarantee not to increase rates of income tax, NICs or VAT. Between them these three bring in almost two-thirds of UK tax revenue. And while there are ways to increase revenue from these taxes without raising the headline rates, this guarantee might prove an unwelcome constraint if adverse economic conditions necessitate tax rises in the next five years, or if they decide they want to change tax rates for other reasons – as Philip Hammond found in 2017 when, following a similar pledge in the Conservatives’ 2015 manifesto, he tried and failed to introduce a modest increase in NICs rates for the self-employed to reduce their tax advantage relative to employees.

Along with this ‘tax guarantee’, the Conservatives’ other main tax policy also involves not doing something: specifically, not going ahead with a further cut in the corporation tax rate, from 19% to 17%, currently due to happen next April.

Beyond that, there is little of note except a modest reduction in employee and self-employed NICs, worth at most £85 a year to affected individuals. The ‘ultimate ambition’ to go much further, increasing the threshold to £12,500 a year, is so far just an ambition, without a firm commitment, a timescale, or a statement of how they would pay for it.

Increasing the NICs threshold is about as well targeted on low earners as it’s possible for a direct tax cut to be, but that is still not very well targeted: only 8% of the gains go to the poorest 20% of working households, and only 3% go to the poorest 20% of all households. Increasing in-work benefits would be much better targeted, though at the cost of extending means-testing to many more people, with all the disadvantages that entails.

Labour

Labour’s offer could hardly be more different. It has ambitious plans for public spending, which come with ambitious plans for tax to pay for them. It would take the UK tax take to its highest ever level, though still not particularly high compared to other Western European countries. But Labour says that there will be no tax increase for 95% of the population.

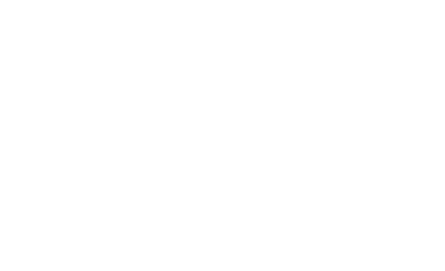

As at the 2017 election, Labour’s headline tax policy is an increase in income tax rates for those with incomes above £80,000 a year (see figure 1). Less noticed is that Labour is also repeating its 2017 proposal for an ‘excessive pay levy’, essentially an employer NICs rise of 2.5 percentage points on earnings above £300,000, 5 percentage points above £500,000 and 7.5 percentage points above £1m.

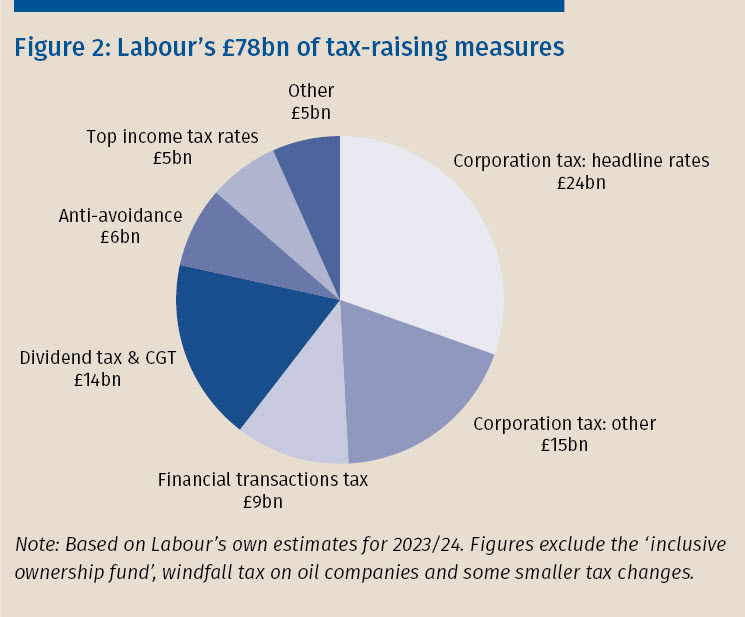

These proposals would affect only the highest-income 5% of taxpayers – indeed only 3% of all adults (those aged 16 or over), since only 58% of adults now receive enough income to pay income tax. The £5bn a year Labour assumes they would raise is plausible, albeit highly uncertain. But this accounts for less than a tenth of the £78bn of additional revenue Labour wants to bring in (see figure 2). Almost half the revenue would come from increases in corporation tax, and more than three quarters from taxes on investment and capital more broadly.

Labour would increase the main rate of corporation tax from 19% to 26% – returning it to its 2011/12 level – and reintroduce a 21% small profits rate for companies with profits below £300,000. That would move the UK’s headline tax rate from one of the lowest in the developed world to above average among OECD countries, but still low by G7 standards. In terms of revenue, however, Labour’s plans would move the UK from raising an average share of national income in corporation tax to the highest in the G7 and one of the highest in the OECD. That is because revenue depends on more than just the headline tax rate. Among other factors, the UK provides less generous capital allowances for big firms’ investment costs than most other countries do. Indeed, while the coalition and Conservative governments since 2010 have spent £13bn cutting the headline rates, they have recouped some £10bn of that by increasing corporation tax in other ways such as reducing capital allowances, restricting loss offsets and introducing the bank surcharge.

Similarly, more than a third of Labour's planned corporation tax increases come from changes other than the rise in the headline rate. This includes £4bn from abolishing the patent box and the R&D tax credit for large firms – to be replaced with direct funding for R&D – and a further £4bn from scaling back other, as yet unspecified, reliefs. The most interesting idea, however, is for a move to unitary taxation of multinationals. This means that, rather than trying to measure and tax their UK profits, Labour would tax a share of the group’s worldwide profits equal to the UK share of other worldwide totals such as sales, employment and tangible assets. These are easier to attach to a particular country, and less internationally mobile, than taxable profits as currently defined. The international corporate tax system does need fundamental reform, and this is one reasonable approach to pursue in multilateral discussions. But international agreement can be difficult to achieve, while introducing unitary taxation unilaterally risks legal challenge and may be impractical anyway. So Labour would be unwise to count on bringing in the £6bn they aim to raise from this.

Labour may also struggle to bring in the revenue it wants from a financial transactions tax. The UK currently raises £4bn a year from the 0.5% stamp duty on shares. Labour wants to extend this to apply (at various rates) to many other financial products including bonds, commodities, foreign exchange and a wide range of derivatives, to worldwide transactions involving UK residents as well as transactions of UK company shares, and to transactions by ‘market makers’ and other intermediaries, which are currently exempt.

Nailing down a precise tax base for derivatives transactions is notoriously difficult, and some of what Labour wants to tax can readily move abroad, casting doubt on whether it would raise the £9bn a year Labour hopes.

More fundamentally, the economic rationale for a transactions tax is weak. Transactions taxes discourage mutually beneficial trades, and the argument that they compensate for this by reducing damaging volatility is theoretically and empirically debatable. Removing the intermediaries exemption is a particularly bad idea. It implies, for example, that shares would be taxed once if bought directly and twice if bought through a broker. Markets are not made more efficient by impeding the matching of buyers to sellers and reducing liquidity.

More welcome is the proposed change to the taxation of dividends and capital gains. Labour plans to tax these at ordinary income tax rates, rather than the much lower rates at which they are currently taxed – including removing entrepreneurs’ relief, forgiveness of CGT at death and other reliefs. This would not quite align overall tax rates between labour and capital income, because income tax is not the only tax in play: labour earnings are also subject to NICs, while dividends and capital gains on shares come from profits on which corporation tax has already been levied. But it would certainly bring the treatment of different income sources much closer together. In the process it would remove much of the incentive for tax-motivated incorporation and the strategic relabelling of income that has become increasingly prevalent – and increasingly costly to the exchequer – in recent years.

Traditionally, one of the main arguments against increasing tax rates on dividends and capital gains was that it would discourage saving and investment. Labour’s proposal counters this by adopting the recommendation of the IFS-led Mirrlees Review to introduce a ‘rate of return allowance’, which allows a ‘normal’ return on investment (specifically, the ten-year gilt yield) to be tax-free and taxes only returns in excess of that. This means that borderline-worthwhile investments would be untaxed, with revenue raised from those highly profitable opportunities that would be worthwhile even after tax. So despite raising large amounts of revenue, Labour’s proposal should actually discourage saving and investment less than the current system. The real disincentive effects of the tax rise would be on business owners’ labour: it would mean taxing their efforts as much as employees’. But as colleagues and I have argued elsewhere, there is no good reason they should be taxed preferentially.

Yet welcome as this direction of reform is, if it is pursued without wide consensus there must be a risk that companies would defer paying dividends, and individuals defer realising capital gains, in the hope that a change of heart or a change of government would lead to the policy’s being abandoned.

There are many other elements of Labour’s proposals, including a windfall tax on oil companies which are now making precious little profit from which to pay it, a 35-point plan to combat tax evasion and avoidance, and an ‘inclusive ownership fund’ which would act like a mandatory employee share scheme for most big companies and more like an additional corporation tax for the minority making (or distributing) unusually large profits per employee. There is not space here for a full analysis of all of them, but a Labour victory would undoubtedly keep tax policymakers, analysts and practitioners busy for years to come.

Taken as a whole, Labour’s tax proposals would certainly not be restricted to 5% of the population as they have claimed. They plan to abolish the marriage allowance, which would mean a £250 a year rise in income tax for 1.8m people – none of whom is in the top 5%, since the allowance is restricted to basic-rate taxpayers. Some of Labour’s other reforms to personal taxation would predominantly affect the better-off, but certainly not be restricted to the top 5%. For example, in 2016/17 (the latest year of published statistics) there were 4.6m taxpayers receiving dividends, around 4m of whom were in the lower-income 95% of the population – although of course those in the top 5% were often receiving much more.

And we cannot ignore those who lose out from corporation tax rises. There is good evidence that part of the burden of corporation tax is passed on to workers in lower wages and customers in higher prices. And to the extent that it isn’t passed on in that way, it means lower profits for shareholders – and that includes small business owners and everyone with a defined contribution pension. Taxes on companies must ultimately be felt by real people, and there is no reason to believe that those people are all among the best-off 5% of the population.

We should be clear: Labour’s tax policies would predominantly affect the better-off. But that is a long way from saying they would only affect the top 5%.

Liberal Democrats

If it weren’t for Labour’s £78bn programme, the Liberal Democrats’ plan for £36bn of measures might be considered a radical tax-raising platform.

They propose a one percentage point increase in all rates of income tax and in the rate of corporation tax. Those are straightforward ways to raise just under half the additional revenue they want to bring in. Most of the remainder comes from three proposals to raise around £5bn each: eliminating the annual exempt amount in CGT, combating tax avoidance (though they do not specify which activities would be taxed more than they are now), and a reform to air passenger duty which would double revenue from the tax while reducing it for those who take one or two international return flights per year. This implies a huge tax increase for more frequent flyers – and an entirely new administrative mechanism to monitor how many flights people have taken in a year.

The Liberal Democrats also propose two major reforms to the tax system which are not intended to raise additional revenue. A proposed reform to business rates – replacing it with a land value tax levied on the property owner – would be welcome in principle, but it involves a major practical challenge: to value the land separately from the buildings on it. And a dedicated tax to fund health and social care sounds nice, but is misguided. There is no reason that spending on a particular item should be linked to revenue from a particular tax.

The Labour and Liberal Democrat tax-raising proposals have elements in common. Both want to increase corporation tax and CGT. Both want to abolish the marriage allowance, increase tax on second homes and extend the soft drinks industry levy (‘sugar tax’) to milk-based drinks. Both want to raise about £6bn a year from clamping down on tax evasion and avoidance. Labour says it would ‘review the option’ of the business rates reform espoused by the Liberal Democrats.

But as well as the obvious difference in scale, there is a difference of approach. The Liberal Democrats’ proposal to add one percentage point to all rates of income tax sends a message that we must all chip in to pay for better public services. Labour, on the other hand, is determined that as far as possible its radical tax rises should fall on companies and the well-off. Meanwhile, on tax – and indeed on public spending – the Conservatives are essentially offering a continuation of the status quo. Stark choices indeed.

This article was originally published on taxjournal.com. You can read the article here.